Back to the Wild

British designer Paul Broadhurst breathed life back into this lakeside garden near Seattle with his environmental approach

AUTHOR: Caroline Beck | January 2018 | PHOTOGRAPHS: Claire Takacs | GARDEN DESIGN JOURNAL | PDF Version

Paul Broadhurst

Paul Broadhurst earned his degree in Environmental Science in London before moving to Washington to pursue a Masters in Landscape Architecture. He is a two-time winner of the ASLA National Design Competition and creates projects in the US, UK and Australia. His passion is in exploring the edges where nature and man meet.

BroadhurstAssociates.com

The 1960s has much to answer for. Brutalist architecture, a conviction that grey concrete complements a northern climate and an approach to environmental issues that makes Donald Trump look enlightened. All these elements reared their ugly heads as British-born designer Paul Broadhurst drew up his plans for a lakeside project in Seattle, on the north-western coast of the US.

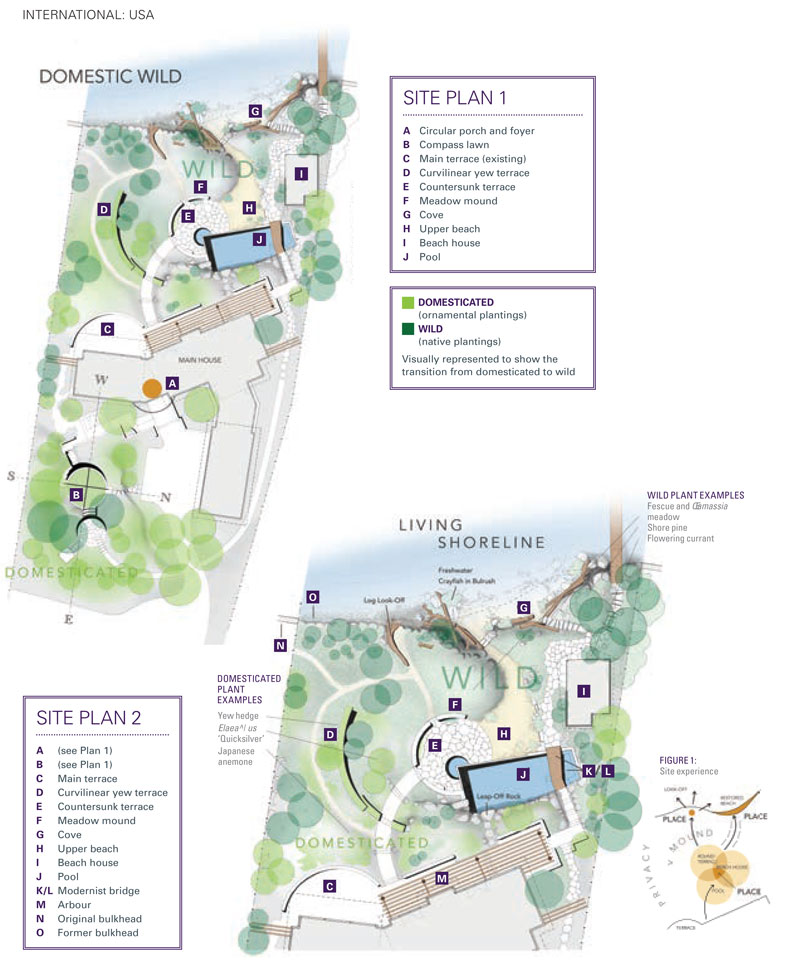

His clients bought a conventional 1960s property overlooking Lake Washington, with a conventional plot to match – a monoculture lawn steeply sloping down to a 50m concrete bulkhead, and a sheer drop to the water. They wanted something more natural, which incorporated a terrace for entertaining and a swimming pool for their children and grandchildren. The inspiration for Broadhurst’s design emerged from some unlikely sources – a classic 1960s book on the environment and an abstract painting by a 19th-century Russian artist. And fish.

In the 60s, when Lake Washington’s shoreline began to fill up with weekend homes, the solution to reducing the impact of waves from passing boats was to build concrete bulkheads, an approach that proved an environmental disaster. “The waves smash into the wall, ricocheting back into the water and scouring the shoreline,” explains Broadhurst. “The sediment can’t build up because of the turbulence, so native plants such as sedges, reeds and willows can’t grow. That impacts upon the number and variety of fish that hang out in the shallows, which in turn means there’s no feeding places for wild birds.” He wanted to soften all the hard edges, re-establish the margins where wildlife could thrive and hence a connection between the house, garden and shoreline.

“HIS URGE TO CONNECT PEOPLE WITH NATURE INVOLVES REDEFINING AND EXPANDING NOTIONS OF WHAT CONSTITUTES VISUAL ATTRACTIVENESS IN A DOMESTIC SETTING”

Environmental ethos

Broadhurst’s ethos is deceptively simple – to link people to their environment through good design. While in London studying for a BSc in Environmental Science, he was profoundly influenced by Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, a howl of rage against the indiscriminate use of synthetic pesticides such as DDT upon the natural world, which ultimately led to its ban. Like millions of others, he was inspired by Carson’s powerfully argued book, making him a lifelong environmentalist. He gave his clients a copy of Carson’s book, A Sense of Wonder, about introducing children (and, by implication, adults) to the natural world – but his urge to connect nature with people involves getting them to redefine and expand notions of what constitutes visual attractiveness in a domestic setting. “My clients’ neighbours were initially very suspicious, even hostile, to what I was doing, because it was such a cultural shift from straight lines to a natural, frayed messiness, but eventually I won them round.”

Winning hearts and minds was one of the project’s less fraught aspects, however. Shoreline projects are notoriously complex and expensive, and numerous obstacles had to be overcome, such as dealing with a sewerage drain located behind the bulkhead. The lake is a spawning ground for protected sockeye salmon, so permits were required for the timing of major construction work to take into account ‘fish windows’ – times in the year when the salmon’s breeding cycle is at its most vulnerable.

Restore the shore

Because there’s no land access, the monolithic bulkhead was removed using a crane on a barge, with rounded rocks and pebbles shipped in the same way, then placed to shelve gently towards the waterline. “The force of the wave action was immediately reduced,” says Broadhurst, “and large woody debris was anchored to the substrate so sediment could gather, creating conditions for plant and fish life to re-establish.” It took just a few months for the shells of crustacea to be washed up on the new beach, followed closely by a wide variety of birds and even an otter.

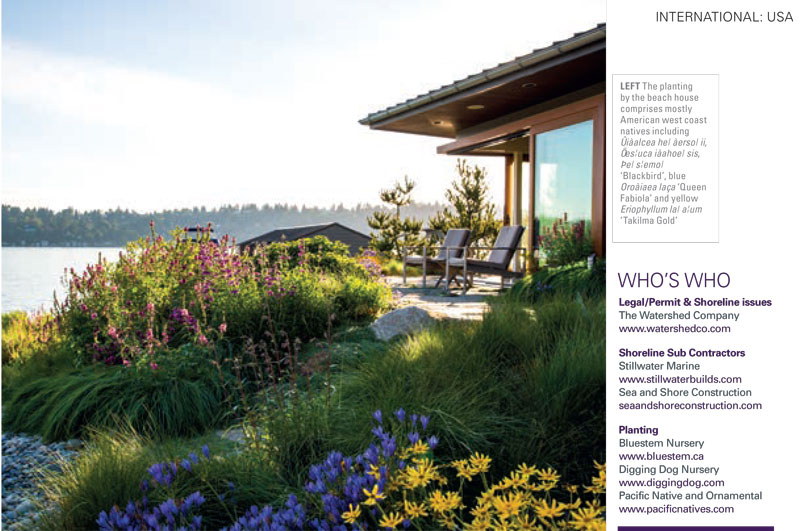

The designer was keen to get rid of the suburban lawn. Its cropped grass was a goose-magnet that created high nitrogen run-off into the water from their droppings, which also made conditions underfoot unpleasant. His plan was to replace some of it with a blend of native grasses and wildflowers. In spring 2016, in a stroke of genius, he kayaked across Puget Sound with his clients and their grandchildren to Yellow Island, a local nature reserve lush with endangered native plants including several species of Camassia leichtlinii, Menzies’ larkspur (Delphinium menziesii), the grass Roemer’s fescue (Festuca roemeri), Oregon iris (Iris tenax) and stonecrops such as Sedum spathulifolium. “It was an immediate change in their perception. They recognised an emotional and cultural connection between plants and people.”

His other influence was artist Wassily Kandinsky’s Composition VIII, a print of which hangs in his studio. The dynamic whirling circles are spliced by geometric lines that appear to spin off from a central point, and this gave him the idea for an infinity pool from which a round terrace and the beach house radiate. The pool, the garden’s still point, reflects both the sky and the lake beyond. It is linked by grasses and wind-sculpted rocks to four flat boulders leading to the pool’s edge, engraved with ‘Look Before You Leap’. The nearby round terrace hunkers down in the landscape, encircled by a native fescue meadow mound, giving the garden a further dimension of sound as the wind moves through the grass.

Broadhurst worked closely with the Green Shores for Homes initiative, a project funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency, which provides help and expertise for homeowners and contractors trying to restore the shoreline. The design has been so successful that it’s now been adopted as an example of best practice, attracting fellow professionals involved in shoreline restoration. But for Broadhurst, success has been measured more subtly. “One day, I disturbed an eight-inch freshwater crayfish in the shallows,” he says, “and another time I saw a ringed plover probing the shoreline, so I know it has all worked.”