Stepping to the Shore

An island off the Washington coast is the setting for a woodland garden.

AUTHOR: Clair Enlow | 2009 August | PDF VERSION

Paul Broadhurst, asla, of Paul R. Broadhurst + Associates, has based his design for the site on the understanding that this reward should not be rushed.

Broadhurst points to one of the larger evergreens on the site, where a large winch is embedded in the bark – a tribute, he says, to the ingenuity of the former owners, who hauled their provisions up from the water. Still reachable only by ferry, Lopez has long been a refuge for artists and independent-minded settlers such as the two women who had made a life for themselves here.

Broadhurst’s work began with a plan that includes a rebuilt and expanded main house, a garage, and a guest cottage. The geology of the shore limits development in a very natural way.

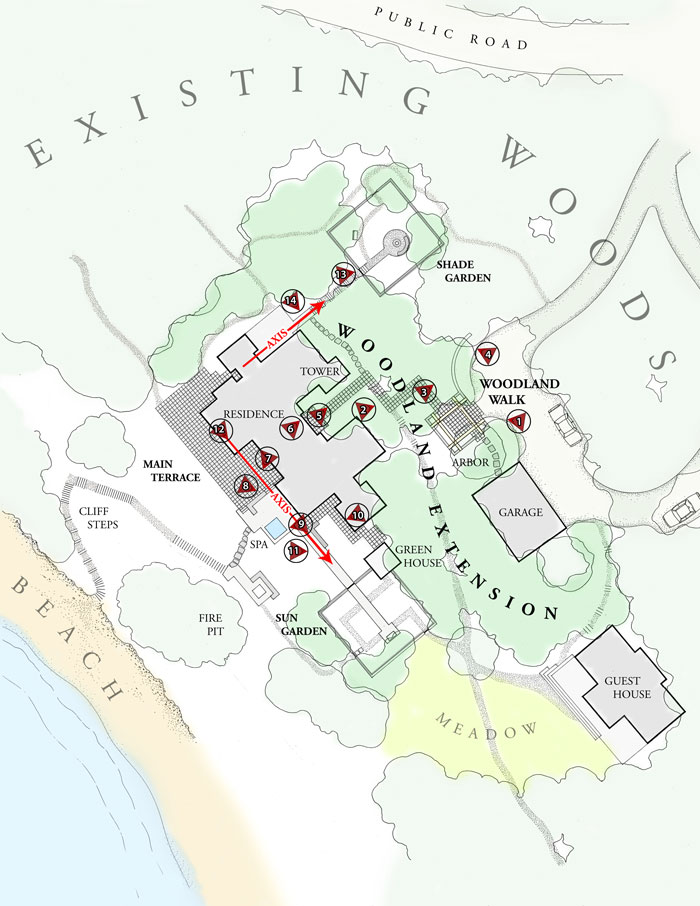

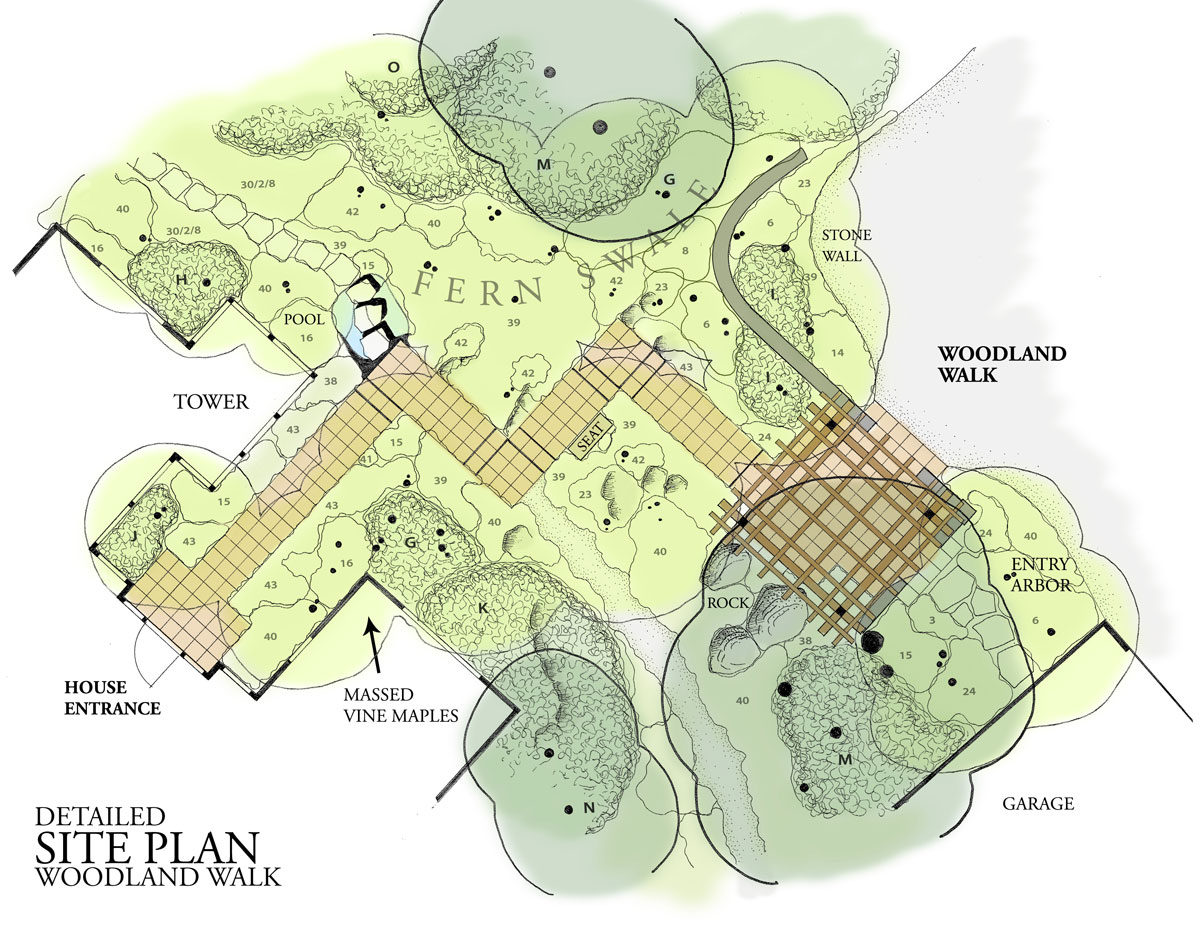

The site narrative begins with the enclosure in the forest and ends with release on the shore. The looped driveway approach to the site is upland and to one side of the compound. A small paved arbor court stands beside the garage, providing an arrival point and setting up the entry sequence. From there, stepped pavers seem poised just above the forest floor, descending lightly into the newly constructed woodland and the entry to the house.

Before reaching the door, a footpath departs to go around the walls, passing the enclosed garden above before joining the expansive waterside patio and its various courts. Either choice – into the front door and the light-flooded interior or around to the other side of the house leads to a sudden encounter with water, sky, and shore. The experience of breaking through to a clearing in the woods is augmented by the sensation of arriving at the edge of a precipice.

As a designer, Broadhurst is obsessed with the margins between built and unbuilt, structure and chaos. This shows in his handling of the concrete steps and pathways through the forest.

From the interior of the house, the result of this land sculpting is to heighten contrast between the cool embrace of the forest on one side and the bright, open view on the other. Broadhurst also paid respect to the legacy of “the ladies,” as he calls the original owners, enclosing a vegetable and cutting garden in a more permanent stone wall precisely where their deer-proof wire fence and garden had been. The pebble mosaic squares of their patio now pave the landing on the steep path to the beach.

The traditional gardening areas desired by the owners (including the original owners’ reinvented vegetable garden) are walled off from the rest of the landscape. In this way, the built environment is tightly controlled so that the woodland areas can be more clearly at one with the native surroundings.

To make a point that applies perfectly to the San Juan House, he likes to quote Gertrude Jekyll: “This is hardly the place for bearded irises!” As influences, he counts Thomas Church, Luis Barragan and Alice Waters. When he dined at her famous restaurant in Berkeley, California, Chez Panisse, “The menu communicated to me where I was and the time of year.”

These choices – a common thread in Broadhurst’s practice – are based on science as well as aesthetics. “What are the niches (ecologically) we are creating in our built landscapes?” he asks, rhetorically. “What plants can best fill these spaces?” He might have chosen any available epimedium for the forest floor. Instead, “Vancouveria (hexandra) fills exactly the same ecological niche.”

By deliberately drawing connections between popular commercial plants and species that are native to the Pacific Northwest, Broadhurst shows how a native plant palette can be applied to a design framework of drifting ground cover, softly mounding midstory plants, and low trees – all under the iconic evergreens.

RESIDENTIAL DESIGN, Honor Award

SAN JUAN ISLAND RESIDENCE

San Juan Islands, Washington

THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT carefully weighed the geological, botanical, historical, and even auditory context of this midsized San Juan Island residence with nearby views of a small horseshoe-shaped bay and distant mountains. The resulting design celebrates the strong views from the site while paying equal attention to the intimacy of the woods. As the view remains blocked by dense forest, a visitor must descend through the forest to the house. The walk offers a meandering engagement in all things minute and intimate. A pathway of local “alger green” rock marks the way. With the exception of two enclosed gardens, local and West Coast native plantings were favored. A “light tower” was a collaborative design element, acting as a beacon at night on the path through the trees to the front door. Ascending the tower takes one above the “forest canopy” and provides a view of the bay. “The landscape architect has created a romantic space with color,” jurors said. “The design is not obvious, which is very difficult to achieve.”